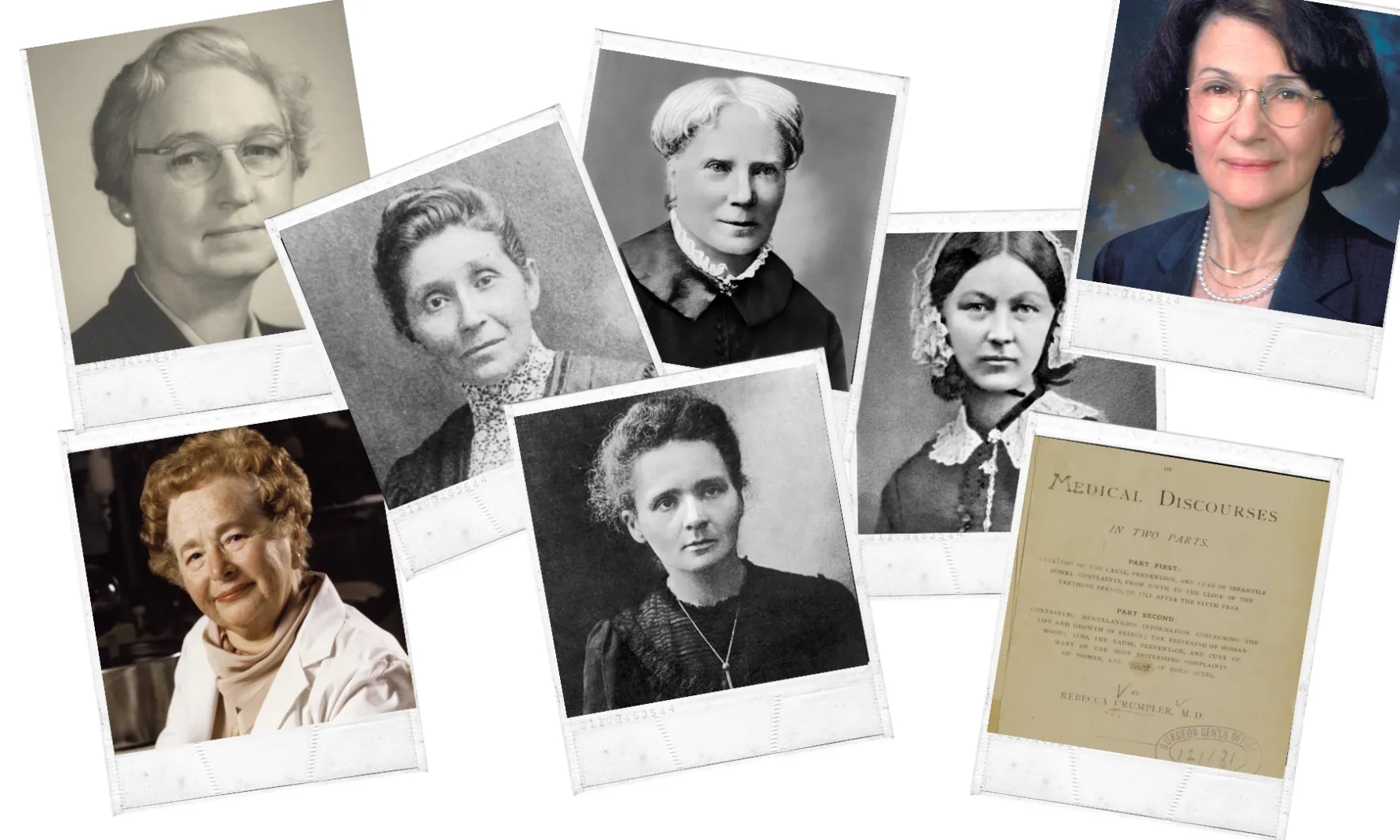

Celebrating Eight Influential Women in Medical History

Throughout history, women have faced prejudice in the scientific and medical communities and were generally excluded from roles except for nursing or midwifery. However, women have been making an impact in the industry since the ancient Greeks. The mid-1850s marked a turning point in society’s view toward women working in science and medicine. So, to kick off Women’s History Month with a bang, we wanted to present eight of the most influential names in scientific and medical history.

Florence Nightingale (1820-1910)

During the Crimean War, Nightingale led a team of 38 nurses caring for injured British soldiers. The male doctors initially scorned the nurses' assistance, convinced that their own methods were more effective. However, due to Nightingale's insistence on new sanitation policies like providing adequate sewers and clean instruments, as well as providing personal attention to each soldier, the death rate at the military hospital dropped from 40% to just 2% in the span of six months.

Nightingale went on to write over 150 nursing books and pamphlets on various health-related issues, making her a prestigious figure regarding hospital sanitation and safety regulations. Two years after her death in 1910, the International Committee of the Red Cross created the Florence Nightingale Medal, awarded to nurses deemed exceptional every two years. Furthermore, International Nurses Day has been celebrated on Nightingale’s birthday since 1965.

Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910)

Elizabeth Blackwell is best known as the US’s first woman to earn a medical degree (MD).

A professor suggested that she disguise herself as a male to gain admission, but she refused, later writing, “It was, to my mind, a moral crusade. It must be pursued in the light of day, and with public sanction, to accomplish its end.”

After facing rejection from several universities, Blackwell was finally accepted to Geneva Medical College in 1847. Although she initially received hostility from her fellow students, she eventually earned their respect and graduated first in her class in 1849.

In 1854, Blackwell, her sister (also a doctor), and Dr. Marie Zakrzewska opened the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. The hospital, and the women’s college that followed in 1867, provided training and experience for women doctors and medical care for the poor.

Rebecca Lee Crumpler (1831- 1895)

Although previously credited to Rebecca Cole, Rebecca Lee Crumpler was the first African American woman in the US to earn an MD. Crumpler gained entrance to the New England Female Medical College in Boston, Massachusetts, after working for eight years as a nurse in nearby Charlestown and receiving several recommendation letters from doctors. When she completed her education in 1864, she became the only black graduate in the school’s history. Following the Civil War, Crumpler moved to Richmond, Virginia, to care for formerly enslaved people.

Although there are no known photos of Crumpler, and little has survived to tell the story of her life, she has secured her place in the historical record with her book of medical advice for women and children, published in 1883.

Susan LaFlesche Picotte (1865- 1915)

Picote, the daughter of an Omaha chief who believed in partnering with white reform groups, studied in New Jersey, and then, at 17, taught at a Quaker school on the Omaha reservation. There, she helped care for ailing ethnologist Alice Cunningham Fletcher, who urged her to pursue medicine. In 1889, after only two years in a three-year program at the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania, she graduated at the top of her class.

Afterward, she returned home, serving a population of more than 1,300 in over 450 square miles, often walking miles and working long into the night. Picote also pursued political reforms, leading a delegation to Washington in 1906 to lobby for prohibiting alcohol on the reservation. In 1913, she opened a hospital in the remote reservation town of Waterhill, Nebraska.

Marie Curie (1867-1934)

Although Marie Curie led a fascinating life, we’ll mention only the medical highlights. In 1898, Marie and her husband Pierre discovered radium, working to understand it despite its ill effects.

During WWI, Marie and her daughter Irene brought mobile X-Ray machines and radiology units to the front line, which allowed more than a million wounded soldiers to be treated.

Curie earned a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903 and yet another in Chemistry in 1911, the first and only woman to have been honored twice. The Curie Institute in Paris, founded in 1920, is still a major cancer research facility today.

Virginia Apgar (1909 – 1974)

Virginia Apgar was determined to become a surgeon. However, she struggled to find a training program when she completed her surgical residency in 1937 because the critical advancement of anesthesiology was not generally recognized as a specialty at the time. In 1938, Dr. Apgar returned to Columbia University as the director of the anesthesia division and as an attending anesthetist, despite facing difficulties recruiting physicians to work for her as surgeons didn’t accept anesthesiologists as equals.

By 1946, anesthesia became an acknowledged medical specialty with required residency training. In 1949, when anesthesia research became an academic department, Dr. Apgar was appointed the first woman full professor at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Apgar began studying obstetrical anesthesia (the effects of anesthesia given to a mother during labor on her newborn baby), where her most significant medical contribution was born. Apgar invented the “Apgar score,” a vital test doctors adopted to examine whether newborn babies required urgent medical attention. The Apgar score is responsible for reducing infant mortality rates considerably and is still used today to assess the clinical condition of newborns in the first few minutes of life. Apgar was also the first woman to become a full professor at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Gertrude Belle Elion (1918-1999)

Gertrude "Trudy" Belle Ellion was inspired to pursue medicine when her grandfather passed away from stomach cancer when she was 15, becoming dedicated to discovering a cure for the disease. Using the methods she had designed, Elion and her team developed a staggering 45 patents, including drugs to combat leukemia, herpes, HIV and AIDS, and treatments to reduce the body's rejection of foreign tissue in kidney transplants between unrelated donors.

In 1988, she shared a Nobel Prize with George H. Hitchins and Sir James Black for their innovative methods of rational drug design, which focused on understanding the target of the drug rather than simply using trial and error.

Patricia Goldman-Rakic (1937- 2003)

Neuroscientist Patricia Goldman-Rakic is most recognized for her studies of the brain, particularly the frontal lobes, and how it relates to memory. Her multidisciplinary research significantly contributed to understanding neurological diseases such as dementia, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s. Her study of dopamine and its effects on the brain is also essential to the modern understanding of conditions such as schizophrenia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Goldman-Rakic co-authored over 300 scholarly articles and co-edited three books.

GetMed is proud to celebrate these powerhouses in the medical field

We know there are many more influential women in the scientific and medical history textbooks— and in the industry today— and we are proud to work in an industry where individuals can inspire innovation and resilience as these women do. Being a healthcare traveler is a tough job, and GetMed is thankful for each person that takes on the role.

Contact us today to learn more about how GetMed can take your healthcare traveler career to the next level.